Editor's Choice

Don't know where to start? The First World War team at Adam Matthew pick some of their personal highlights from the collection.

Module II: Propaganda and Recruitment

Module III: Visual Perspectives and Narratives

Module II: Propaganda and Recruitment

The Art of Visual Persuasion: Powerful Propaganda and the Great War

Sarah Mellowes

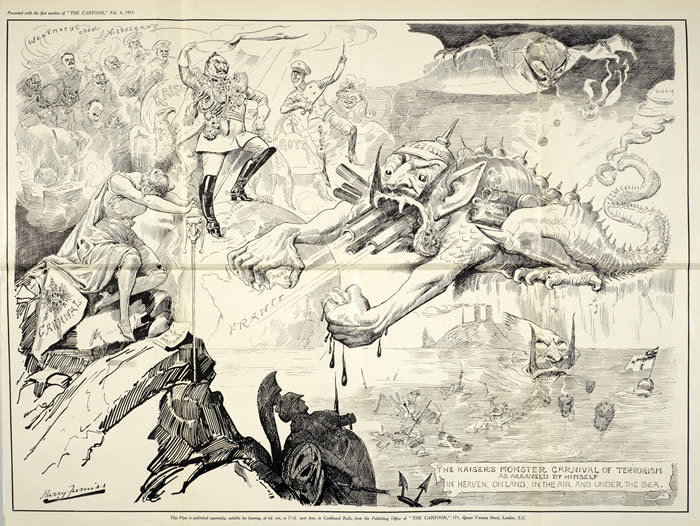

Propaganda was, and still is, used as an incredibly effective tool on multiple levels: to exploit existing beliefs; establish authority; create fear; use humour; appeal to patriotism; to be selective and create a ‘version’ of the truth; to name but a few. Among the diverse range of material within this collection, a personal highlight is the visual propaganda, notably the illustrations and caricatures; some of which are daringly bold, and others intricate in detail, but equally significant in their desired effect on the civilian, soldier and enemy. Alongside the boom in commercial advertising during the Great War, the turbulent period offered artists a fertile ground, as their talent became an essential cog in the wheel of the propaganda machine.

Propaganda was, and still is, used as an incredibly effective tool on multiple levels: to exploit existing beliefs; establish authority; create fear; use humour; appeal to patriotism; to be selective and create a ‘version’ of the truth; to name but a few. Among the diverse range of material within this collection, a personal highlight is the visual propaganda, notably the illustrations and caricatures; some of which are daringly bold, and others intricate in detail, but equally significant in their desired effect on the civilian, soldier and enemy. Alongside the boom in commercial advertising during the Great War, the turbulent period offered artists a fertile ground, as their talent became an essential cog in the wheel of the propaganda machine.

This resource showcases the work of many war cartoonists and illustrators, featured in books and periodicals, as well as on posters and postcards. Striking examples of differing illustrative propaganda methods can be viewed in the works of Harry Furniss and Bruce Bairnsfather. Furniss’s work, which featured in Punch magazine and the periodical The Cartoon (featuring in our Cambridge University Library collection), often used the powerful propaganda weapon of demonising the enemy. The Kaiser (often representing ‘the Germans’) is depicted in a devilish form; Belgium is literally crushed by the hand of Germany’s ruler; a personification of ‘Truth’ is held captive, never to be freed unless his enemies are victorious.

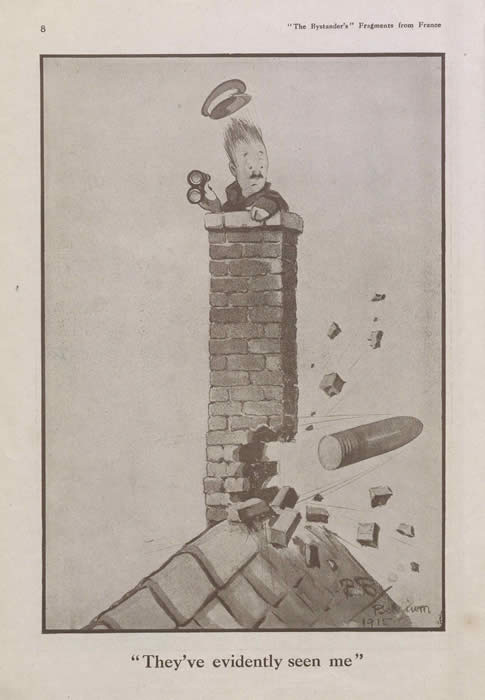

From stereotyping the enemy to illustrating the glories of combat, the propaganda machine only strengthened as mobilisation spread. In contrast to the demonic depictions in the work of artists such as Harry Furniss and Louis Raemaekers, many works employed a comedic approach in an attempt to soften tensions and displace fear on the home front and on the battlefields. Bruce Bairnsfather achieved significant recognition for his humorous artwork within The Bystander’s Fragments from France series, six volumes of which feature in our resource, sourced from the Robert Opie collection. Whilst a huge number of cartoons took the form of political satire to hit home certain messages, Bairnsfather, on the other hand, turned to his fellow soldiers as the subject of his art, rather than the enemy.

This approach was highly effective for morale and patriotism at home and in the trenches. The editor notes in the fourth volume, ‘Bairnsfather has seen in [his characters] the simple man caught in the vortex of a war of unaccustomed complexity, and shown them to us in proof that human nature and humour survive in the heart of horrors’. The editor also stresses in an earlier volume, ‘Those who would have us simplify ourselves upon the continental model, and present to the world a picture of sombre seriousness, are asking us to change our national character. Cromwell asked the painter to paint him, “warts and all”. Bairnsfather sketches us – smiles and all.’ Similar to many propaganda posters at the time, artists had to strike a delicate balance of positive messages in order to maintain continual recruitment and morale, and revealing only small (and often light-hearted) snapshots of the soldiers’ experiences in order to stabilise the domestic war effort. Perhaps the key to Bairnsfather’s success was that his characters were ‘seriously comical and comically serious’.

There was an old Kaiser who lived in a shoe... Propaganda for Children

Sophie Smith

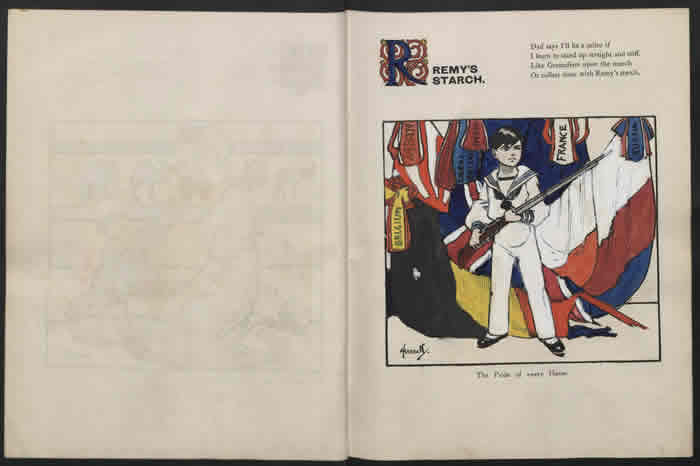

One thing which surprised me when working with the Robert Opie Collection for this project was the huge variety of propaganda material produced in Britain. Whilst posters and pamphlets are well-known mediums, the propaganda machine also churned out badges, decorative pins, mugs, packaging, stamps… the list goes on. All were intended to promote patriotism and a particular view of the enemy, in order to maintain support for the war on the home front. The items which particularly caught my attention were those aimed at children. Themed alphabet books, cartoon characters such as the Peek-A-Boos, and board games all encouraged the divide between “us” and “them”, and a positive, pro-active attitude towards the war and the war effort.

One thing which surprised me when working with the Robert Opie Collection for this project was the huge variety of propaganda material produced in Britain. Whilst posters and pamphlets are well-known mediums, the propaganda machine also churned out badges, decorative pins, mugs, packaging, stamps… the list goes on. All were intended to promote patriotism and a particular view of the enemy, in order to maintain support for the war on the home front. The items which particularly caught my attention were those aimed at children. Themed alphabet books, cartoon characters such as the Peek-A-Boos, and board games all encouraged the divide between “us” and “them”, and a positive, pro-active attitude towards the war and the war effort.

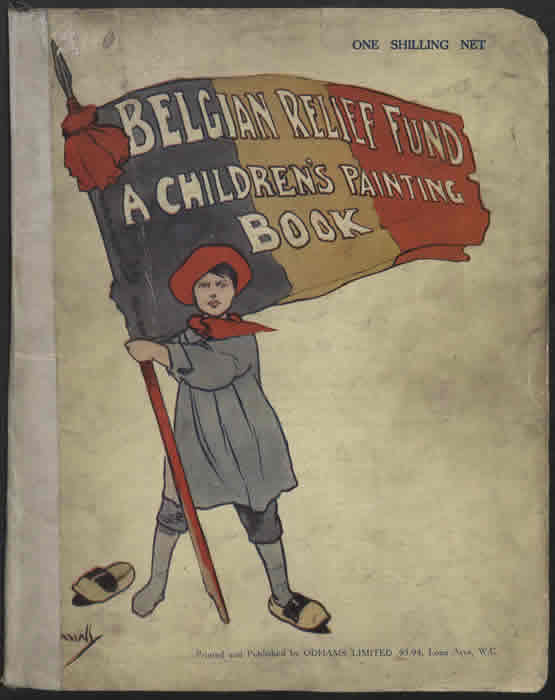

One charming document is A Children’s Painting Book, which features cartoons advertising British products, sold in aid of the Belgian Relief Fund. This was one of many ways in which children were involved in and contributed to the war. The alphabet painting book, completed by a certain Phyllis Mainwood, aged nine, was entered into a competition and also contains a letter from her father certifying that it was indeed his daughter’s work. Unfortunately we do not know how she fared in the competition, but this book was one of the many ways that children were approached in order to educate them about the war and their own country’s part in it. As well as encouraging patriotism and a courageous attitude in the face of the enemy, the book also promotes British manufacturing.

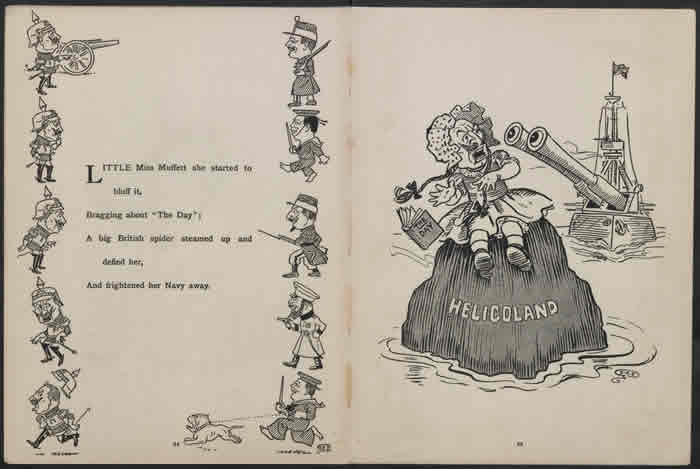

Another creative approach towards propaganda for children can be seen in Elphinstone Thorpe’s Nursery Rhymes for Fighting Times, which manipulates well-known British rhymes in order to belittle the enemy’s efforts and elevate those of the Allies.

Another creative approach towards propaganda for children can be seen in Elphinstone Thorpe’s Nursery Rhymes for Fighting Times, which manipulates well-known British rhymes in order to belittle the enemy’s efforts and elevate those of the Allies.

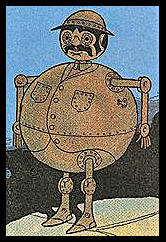

Here, another aim of the propaganda for children seems clear: by making fun of the enemy, the danger appears reduced and the chances of success increased. As Thorpe writes in her introduction, “At times of great national stress, a little nonsense may occasionally prove an excellent tonic”, and this was particularly necessary for children whose families were torn apart and who faced the threat of the German planes and zeppelins overhead. The author blends the familiarity of the nursery rhyme patterns with humorous alternative lyrics, creating a satirical view of the war which must have resonated as much with adults as with children. If the reader was in any doubt of the meanings of the rhymes, each is accompanied by a cartoon (drawn by G.A. Stevens) which ridicules the figure of Kaiser Wilhelm II and shows the British and Allies as heroes. Whilst some of the rhymes are very funny, others are surprisingly dark for a children’s book, such as “Puffing Billy” (Kaiser Wilhelm II) who is described as having “blood on his fingers and shells for his foes”.

Children, it would seem, were considered just as vital to the war effort as adults and merited just as much attention when it came to propaganda. They contributed to charitable funds for civilians and soldiers abroad, and it was essential that the whole of Britain was united in their belief in the nation and the war effort. These two documents also show the creativity of the propaganda produced, which endeavoured to influence the whole country, whether through serious and earnest appeals or through humour.

The Secrets of German Censorship: Military Files from the Landesarchiv Baden-Württemberg

Georgina Phipps

Normally, the only interaction the general public have with propaganda is as recipients of the finished, carefully crafted product: “Your Country Needs You”; “Halt the Hun!”; “Daddy, what did YOU do in the war?” Such stirring patriotic motifs and bold images of national leaders pinning us with accusatory stares are all instantly recognisable. Less familiar are the machinations of the world which produces them: the dark, secretive corridors of government press and propaganda departments.

Normally, the only interaction the general public have with propaganda is as recipients of the finished, carefully crafted product: “Your Country Needs You”; “Halt the Hun!”; “Daddy, what did YOU do in the war?” Such stirring patriotic motifs and bold images of national leaders pinning us with accusatory stares are all instantly recognisable. Less familiar are the machinations of the world which produces them: the dark, secretive corridors of government press and propaganda departments.

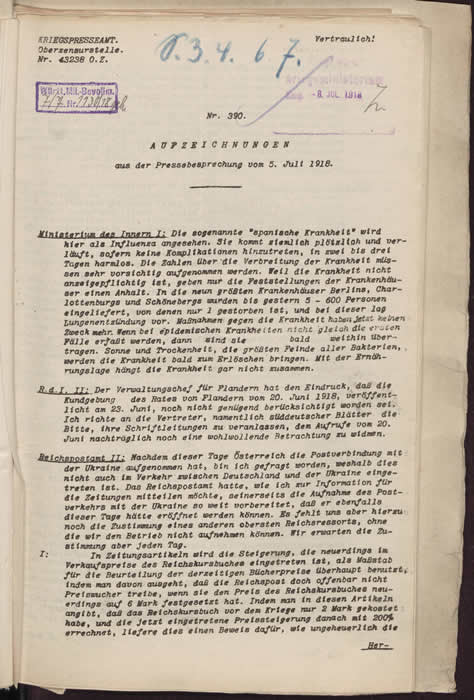

The First World War: Propaganda and Recruitment offers such a rare ‘behind-the-scenes’ tour through several ‘patriotic service and war propaganda’ files from the Landesarchiv Baden-Württemberg. These include reports and instructions of the German war press office in Berlin, minutes of press conferences, and censorship directions from military authorities. Not only do they provide a rare insight into how a wartime government responded to calamitous events from military setbacks to the Spanish flu, but they also reveal the consequences these responses would have for German and world history.

Propaganda during the war fell under the remit of the Supreme Command of the Army (the OHL). In October 1915, the OHL established a War Press Office to provide controlled information on military matters and facilitate cooperation with civilian authorities; though as by 1916 the OHL had superseded civilian and monarchical power as Germany’s de facto government, the War Press Office became the nation’s central authority on information and censorship not just of military issues, but civilian also. In an effort to prevent internal unrest at home and bolster troop morale at the front, the OHL’s press office suppressed reporting on everything from strikes and food shortages to war aims and military defeats – and their work was highly effective. When the country’s leading newspapermen were assembled at a press conference on the 4th October 1918 and told the full truth of the military situation, the shock was severe. Interestingly, the files from the Landesarchiv reveal that even after OHL had admitted to the press that the war was lost, they still seemed determined to conceal the full extent of Germany’s collapse from the public, right up until the very last days of the war.

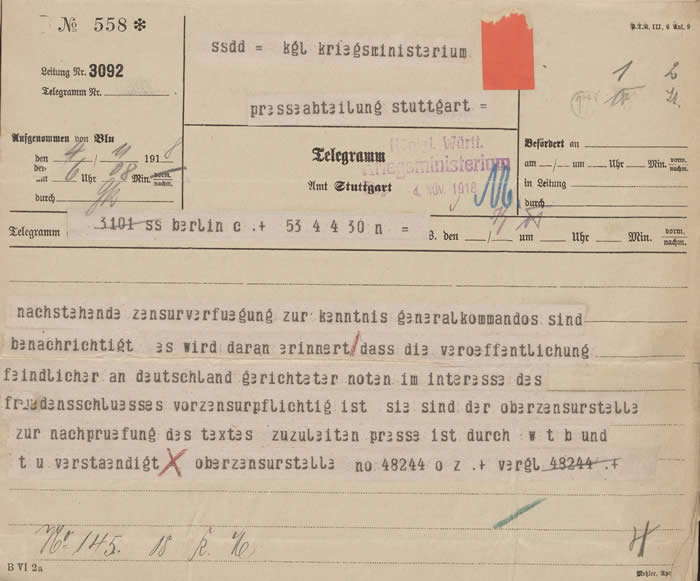

In File M 1/3 Bü 564, a collection of regulations and instructions from the Supreme Censorship Office in Berlin, is a telegram dated 1st November 1918 forbidding reporting on the refusal of Austro-Hungarian troops to continue fighting. A telegram of the 4th November prohibits all foreign notes respecting the armistice from being published lest the truth of the harsh terms become known, while another of the same day prohibited newspapers from reporting on “events in Kiel” – the events being a mutiny in the navy. A telegram of the following day extended the censorship of the Kiel mutiny by briefly stating that all reports on street demonstrations and protests remained subject to censorship.

In File M 1/3 Bü 564, a collection of regulations and instructions from the Supreme Censorship Office in Berlin, is a telegram dated 1st November 1918 forbidding reporting on the refusal of Austro-Hungarian troops to continue fighting. A telegram of the 4th November prohibits all foreign notes respecting the armistice from being published lest the truth of the harsh terms become known, while another of the same day prohibited newspapers from reporting on “events in Kiel” – the events being a mutiny in the navy. A telegram of the following day extended the censorship of the Kiel mutiny by briefly stating that all reports on street demonstrations and protests remained subject to censorship.

Thus even after the OHL had driven Germany to defeat and lost its grip on power, the military still controlled censorship and sought to conceal the reasons for defeat, the extent of Germany’s collapse, and the humiliating conditions of the armistice.

The apparent suddenness of defeat, and the OHL’s distancing of themselves from responsibility through their censorship campaign, contributed significantly to the ‘stab-in-the-back’ myth: the belief that Germany had not been militarily defeated but had instead been betrayed by a conspiracy of pacifists, Jews and Bolsheviks on the Home Front. Such a belief would destabilise politics and society for the next 15 years and critically undermine Germany’s first experiment with democracy.

The Nine Qualities of the Super-Citizen Soldier: The Making of a Real Life Tik-Tok?

Xavier Snowman

Within only a few months of the US entering the First World War, it became clear to congress that only the introduction of mass conscription would draw together enough manpower for the cause. The introduction of conscription during the Civil War had stirred widespread disapproval, opposition and conflict, with many likening it to slavery. A tactful implementation was crucial, and so the Selective Service Bill was passed, placing the responsibility for registration of males between the ages of 21 and 30 in the hands of local civilian registration boards.

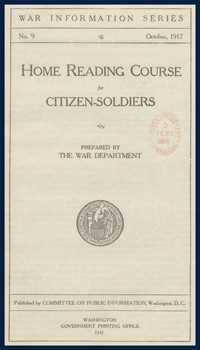

The War Office released a number of publications devoted to readying eligible civilians for military life, one of which takes a didactic approach by providing “30 daily lessons… as a practical help in getting started in the right way”. The Home Reading Course for Citizen Soldiers outlines the 9 essential qualities of a soldier, some of which – at least to me – seem indistinct, un-cultivatable and, in many ways, automaton in that they don’t account for any sort of emotion other than a sense of unyielding patriotism and cheerfulness.

The War Office released a number of publications devoted to readying eligible civilians for military life, one of which takes a didactic approach by providing “30 daily lessons… as a practical help in getting started in the right way”. The Home Reading Course for Citizen Soldiers outlines the 9 essential qualities of a soldier, some of which – at least to me – seem indistinct, un-cultivatable and, in many ways, automaton in that they don’t account for any sort of emotion other than a sense of unyielding patriotism and cheerfulness.

After reading this pamphlet, I envisaged a sort of indoctrinated, super-obedient and relentlessly jolly robot. Actually, Lyman Frank Baum’s Wizard of Oz character, ‘Tik-Tok’ springs to mind. Tik-Tok is a prototype war machine, personified as a jolly British officer who needs his three mechanisms (thought, action and speech) winding up in order to fight effectively.

In the Home Reading Course for Citizen Soldiers, “Loyalty”, “obedience” and “physical fitness” are outlined as the most basic and essential qualities. “A man without these qualities is in the way and is a source of weakness to an army.” The next three qualities – “intelligence”, “cleanliness” and “cheerfulness” – are outlined as being “especially needed.” Finally, there are three further qualities that mark the difference between a “camp-fire soldier” and a “good soldier.” These are “spirit”, “tenacity” and “self-reliance.”

“Spirit” is defined as a “cool, self-controlled courage—the kind of courage that enables a man to shoot as straight on the battlefield as he does in targetpractice.” According to the author, this spirit can be taught and developed “until it becomes as much a part of yourself as any of your easy-going civilianhabits are now.” Surely not? Could shooting true and straight at another Human Being become as easy as shooting at an inanimate, sort of man-shaped target? Could it really become so ordinary, so natural a habit as nodding to your Next Door Neighbour?

“Spirit” is defined as that which carries a body of soldiers forward, but “tenacity” is what makes them stick. According to this publication, tenacity is that which makes a soldier never ready to stop fighting until his part of the battle is won. The words of John Paul Jones are cited, who, standing on his sinking ship amongst his piles of dead allies answered his adversary’s invitation of surrender: “Sir, I have not yet begun to fight.” So in the heat of battle, when all seems hopeless and lost, the perfect soldier won’t take the opportunity to surrender, they’ll just find enough cheerful resolve to keep going it alone.

Module III: Visual Perspectives and Narratives

Impressions of War: The Artist's Perspective

Sarah Mellowes

Amidst the violence and irrevocable change borne out of the First World War, an eclectic range of creative expressions came into existence; from realistic depictions to expressionist works in the form of oil paintings, watercolours, pastels and pencil sketches. This resource showcases the work of many key artists, as well as those lesser-known artists, who were a part of the war art schemes developed by the British government during the war. Recording impressions of the Western Front battlefields and ruins, as well as harsh civilian realities, artists such as Anna Airy, William Orpen and Olive Mudie-Cooke revealed their own diverse experiences as eye-witnesses to war.

In addition to the artwork, a wealth of artists’ commissioning files can be explored, including material relating to the inspection, transportation, exhibition and copyright of the work they produced, providing both a fascinating and significant contextual background to the art pieces. Documents from the British War Memorials Committee show the selection process of many subjects they believed should be represented, from the front lines to the munitions factories, as well as the allocation of subjects to artists. A key member of the committee, Mr Arnold Burnett, expressed the importance of depicting everyday work life during wartime: ‘The large munitions works has its complete life, which is full of interesting scenes scarcely to be noticed’. Consequently, Anna Airy would depict several factory scenes, and in the process of painting, witness her shoes melt off her feet in the intense heat.

In addition to the artwork, a wealth of artists’ commissioning files can be explored, including material relating to the inspection, transportation, exhibition and copyright of the work they produced, providing both a fascinating and significant contextual background to the art pieces. Documents from the British War Memorials Committee show the selection process of many subjects they believed should be represented, from the front lines to the munitions factories, as well as the allocation of subjects to artists. A key member of the committee, Mr Arnold Burnett, expressed the importance of depicting everyday work life during wartime: ‘The large munitions works has its complete life, which is full of interesting scenes scarcely to be noticed’. Consequently, Anna Airy would depict several factory scenes, and in the process of painting, witness her shoes melt off her feet in the intense heat.

Some files provide glimpses of an artist’s background, and also indicate their ongoing post-war activities. Such is the case with Olive Mudie-Cooke, one of the few female official war artists who served as a volunteer ambulance driver at the front. Her personality and passion to communicate intimate responses to war reveals that she was someone who didn’t necessarily follow tradition, but who, ‘being able to follow her own inclinations, preferred, with her keen interest in life, to travel and observe’ (G. Clausen, October 1916). Also, her commitment to her wartime experience is shown in one of her letters, from November 1920, where she requests permission from the IWM to include a painting of VAD ambulances in a souvenir album she is creating for the VAD ambulance drivers with whom she worked with.

Some files provide glimpses of an artist’s background, and also indicate their ongoing post-war activities. Such is the case with Olive Mudie-Cooke, one of the few female official war artists who served as a volunteer ambulance driver at the front. Her personality and passion to communicate intimate responses to war reveals that she was someone who didn’t necessarily follow tradition, but who, ‘being able to follow her own inclinations, preferred, with her keen interest in life, to travel and observe’ (G. Clausen, October 1916). Also, her commitment to her wartime experience is shown in one of her letters, from November 1920, where she requests permission from the IWM to include a painting of VAD ambulances in a souvenir album she is creating for the VAD ambulance drivers with whom she worked with.

Fully aware of the devastating effects of war, William Orpen, one of the earliest commissioned artists, recognised the temporary nature of war, noting that certain witnessed scenes were ‘of certain interest in so much as the subject never can or will be done again’ (October 1917). By 1917, Orpen had produced many canvases and drawings and wanted to present them on the condition that he remain in France working for the British government. His correspondence conveys a slight sense of disenchantment in conforming to instructions from the government. Artists yearned to support the national cause, but their natural feelings of curiosity and interest could not be stifled, and they felt an urgency to capture unique moments in time. Charles Masterman, however, knew that other artists were ‘madly jealous’ of Orpen's war artist role (May 1917), and sought to quickly reproduce his work in order to justify his presence there.

From artist’s files packed with correspondence and contractual agreements, to exhibition folders brimming with press cuttings showing the reception of their art on the Home Front, these documents play an essential role in offering a 'behind-the-scenes' perspective on their work. Although perhaps feeling like a silent witness whilst producing the art, their depictions would inevitably speak volumes about the harrowing nature of war and a society forever changed.

What an Army! An Engineer’s Observations on the Western Front

Sarah Buckman

Secrecy at the Front was paramount. Letters were subject to rigorous screening by Army censors, with movements, casualties and place names scrubbed from missives – a practice instrumental in coining the well-known address, ‘Somewhere in France’. Troops granted leave returned home with strict orders not to discuss their experiences, with breaches leading to immediate reprimand and recall. Diaries too were prohibited, although this was largely ignored and many men continued to keep these deeply personal records.

Secrecy at the Front was paramount. Letters were subject to rigorous screening by Army censors, with movements, casualties and place names scrubbed from missives – a practice instrumental in coining the well-known address, ‘Somewhere in France’. Troops granted leave returned home with strict orders not to discuss their experiences, with breaches leading to immediate reprimand and recall. Diaries too were prohibited, although this was largely ignored and many men continued to keep these deeply personal records.

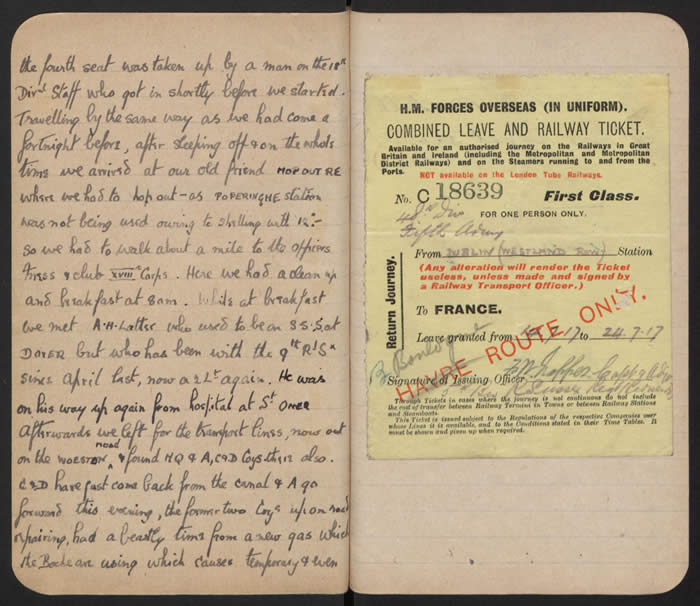

The diaries of Second Lieutenant Gerald Brunskill (available in First World War: Visual Perspectives and Narratives) provide an unbroken record of events whilst stationed as an engineer and observation officer in France, Belgium and Italy. Destined eventually to reach the lofty rank of Major General, Brunskill joined the 5th Battalion Royal Sussex Regiment in 1914; before his 18th birthday!

Richly detailed and written with jocular humour, (his catchphrase ‘What an Army!’ used at regular intervals to describe particular incidences of army stupidity), the diaries chart his training in camps at Hastings and elsewhere before being posted to France in late 1916. Diary 32 (24 July to 18 August 1917) is particularly illuminating, coving the lead up to the Third Battle of Ypres.

Posted to the Ypres area, Brunskill leads a working party laying railway track before the ‘stunt’ begins. He vividly records the sights; the ‘smelly drain’ of Poperinghe Canal and the unpleasant shelling their positions receive. Listening to the beginning of the battle, his description from 31 July is as thrilling as it is chilling: “Shortly before 4 am we were woken up by a terrific bombardment which told us the stunt had begun. This increased in magnitude to a perfect tornado, immediately preceding the infantry attack ….” After a successful initial push, Brunskill is sent forward on 12 August for observation, describing the abandoned German trenches as “… exceptionally good, in some places concreted trenches elsewhere strongly revetted with high hurdlework held in position by strong timbers or stakes firmly driven into the ground: His M.G. emplacements were wonderful efforts, made of reinforced concrete, in shape like a pill box or tall hat, which can resist even a direct hit from the smaller shells ...”

can resist even a direct hit from the smaller shells ...”

This level of precise detail makes these diaries invaluable. His descriptions are matter-of-fact and full of British stiff upper lip. Assisting stretcher bearers to bring in a seriously wounded comrade, Brunskill remarks appreciatively that the boy was "... sticking it gamely." His assessments of the damage done to Belgium are eye-opening and horrific. On 10 August, he wrote “Peronne was bad and Bapaume was worse, but undoubtedly Ypres for an example of Hun frightfulness takes the cake absolutely … nothing but the jagged remains of walls, rising amid piles of rubble and filth remain to remind you that this was Ypres.”

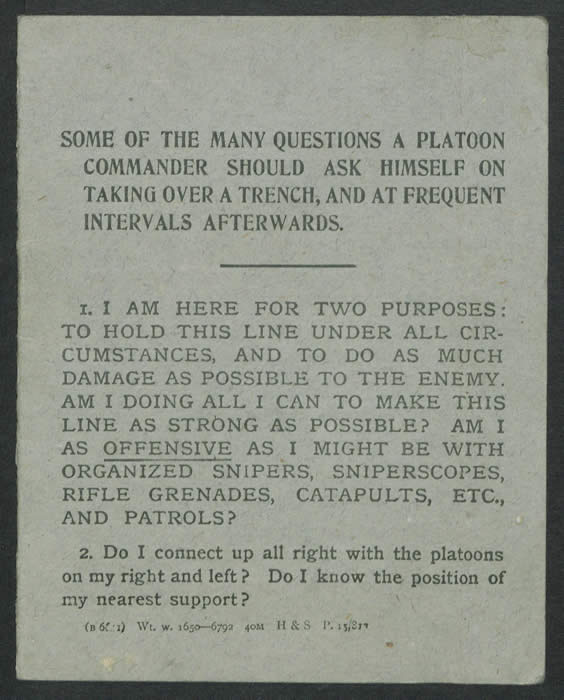

Pasted within these diaries are various Army publications and Diary 32 is no exception, including printed questions an officer should ask himself whenever occupying a new trench. This leaflet was parodied by the popular trench newspaper, the Wipers Times in the cartoon ‘Am I as offensive as I might be?’

Brunskill’s diaries offer unprecedented access to an eye witness narrative of daily Army life. They are witty, exceptionally detailed and an essential read for any First World War scholar.

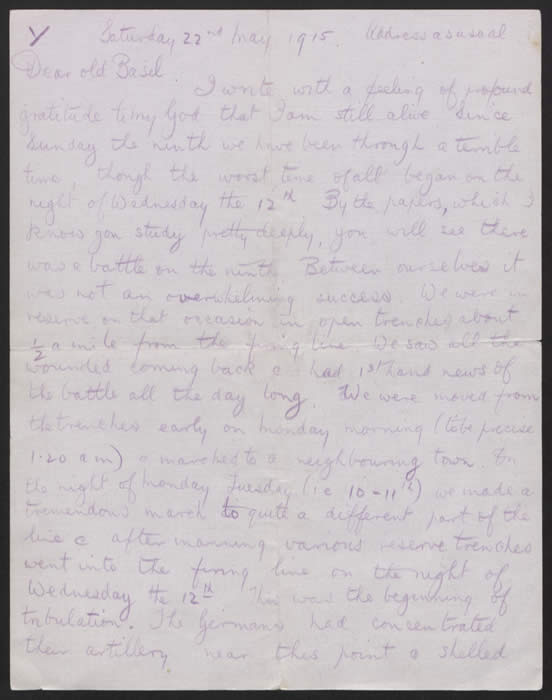

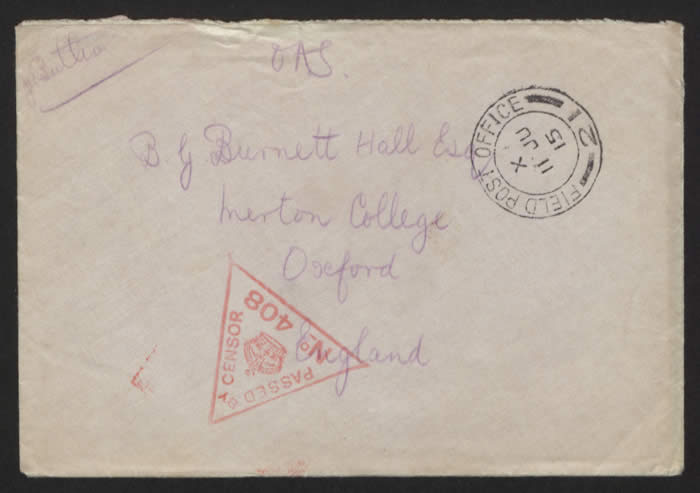

Dear Old Basil: Letters from Lieutenant James H Butlin

Sophie Smith

All the correspondence that I have worked with in First World War: Visual Perspectives and Narrative has been fascinating, but one collection in particular caught my attention. Within the Private Papers of Lieutenant J H Butlin are letters written throughout the war by James to his close friend and confidante, Basil Burnett Hall, which stand out as being surprisingly frank and open, despite the threat of the censor. James writes in ebullient tones about his experiences (both on base and off) in training with the 3rd Battalion  Dorsetshire Regiment based at Wyke Regis before active service in France as a subaltern. Some of the comments made me smile when indexing, such as his need to inform Basil that “I shaved my moustache off this morning. It had got to a great size and prevented me from seeing properly” (20 September 1914). He makes regular references to his amorous pursuits, and declares himself to be violently in love with a variety of women before beginning a more genuine affair with a French girl, Juliette.

Dorsetshire Regiment based at Wyke Regis before active service in France as a subaltern. Some of the comments made me smile when indexing, such as his need to inform Basil that “I shaved my moustache off this morning. It had got to a great size and prevented me from seeing properly” (20 September 1914). He makes regular references to his amorous pursuits, and declares himself to be violently in love with a variety of women before beginning a more genuine affair with a French girl, Juliette.

The letters are very witty and often light-hearted – even Basil’s avoidance of conscription is made fun of (“you still succeed in hoodwinking the doctors that you are weak and puny” (9 December 1915)) and James’ reaction to going to France is that “it will be a nice holiday without much expense” (15 March 1915) – but as the war rumbles on it becomes clear that James’ experiences on the Western Front begin to take their toll. He writes extremely (and surprisingly, given the rigid censorship) detailed accounts of the Battles of Festubert (May 1915) and Arras, desiring to acquaint his friend of the horrific realities of those battles rather than the government-approved versions – "between ourselves it was not an overwhelming success". At Festubert the British artillery shelled their own trenches by mistake, killing so many men “it was impossible to bury the dead” (22 May 1915). He later writes an unusually serious letter before going into battle, requesting that Basil write to Juliette if he is killed, and to burn the letter if he survives (9 April 1917). The letter wasn’t burnt although he did survive the battle. James’ attempts at joviality become more forced and it is not altogether surprising to learn that he is evacuated back to England suffering from shell-shock. He writes after the Battle of Arras that “at present I am a bit nervy and want all the rest I can get” (16 April 1917).

This correspondence succeeds in both entertaining and enlightening the reader, revealing the hopes, fears and experiences of young men in wartime. It shows the vital need to enjoy life where possible, even in hellish conditions, and the importance and comfort of a friend back home to whom feelings could be freely expressed. Well worth a read!

From the Trenches to the Hospitals: Watching the Work of the Red Cross

Ben Lacey

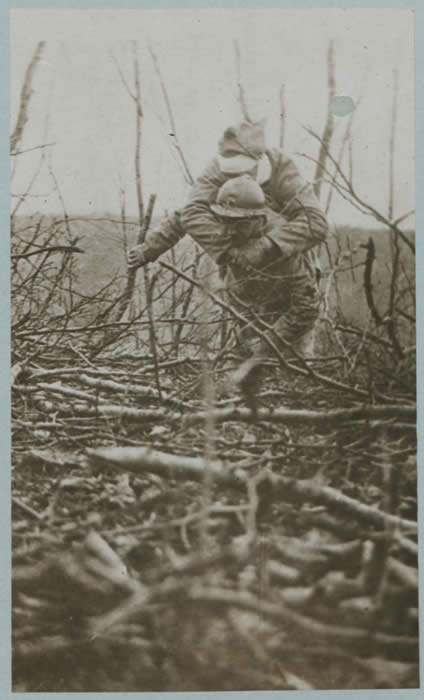

The various national divisions of the Red Cross provided vital medical services during the First World War. The Red Cross and Military Medical Services Album 1 contains photographs of Red Cross and military medical workers in action. The images tell the story of care for the wounded from the front line to convalescent homes. The album starts with a picture of a French Red Cross worker carrying a wounded soldier on his back. He struggles through thick mud and undergrowth in order to remove the soldier from harm. This sets the tone for a document that gives a feel for the difficult tasks carried out by medical personnel.

The various national divisions of the Red Cross provided vital medical services during the First World War. The Red Cross and Military Medical Services Album 1 contains photographs of Red Cross and military medical workers in action. The images tell the story of care for the wounded from the front line to convalescent homes. The album starts with a picture of a French Red Cross worker carrying a wounded soldier on his back. He struggles through thick mud and undergrowth in order to remove the soldier from harm. This sets the tone for a document that gives a feel for the difficult tasks carried out by medical personnel.

Casualties in the trenches were initially treated at Red Cross advanced stations. The album contains photos of just such a station in a French trench. It also has images of a subterranean dressing station being built and an advanced dressing station in the Italian mountains. Strong dugouts were built in order to provide places of immediate medical assistance for the wounded. Urgent operations took place near the front line, in Red Cross tents. Those who survived were then moved to the rear of the trenches for further care.

In the midst of the trauma of war, there were still occasional moments of relief. One picture in this album offers a thoroughly British scene set against the backdrop of Italian mountains. A Colonel of a field ambulance unit invited two nursing sisters from the advanced dressing centre to tea. The photo shows the small party sat up to a table bedecked in a pristine white tablecloth, flowers and a china tea set. Even the awkward gradient of their location does not seem to have caused too many problems.

Moving away from the front, the Red Cross provided transport for those who survived their injuries. Hospital trains, canal boats and ships  are all pictured. The images also show the preparations made at stations before the hospital trains arrived, the removal of casualties from the train and the carrying of the wounded on to ambulances. From the station the wounded were taken to hospital. The Queen’s Hospital for Sailors and Soldiers in Kent features prominently in this album. This was a place where men who had suffered facial or head injuries could be treated. From here, soldiers were moved to a clearing hospital in Eastleigh, Hampshire. The final stage of treatment was provided by convalescent homes, such as the Hotel Burdon at Weymouth. Convalescence might also mean a trip out. The Red Cross Outings Society of Cairo organised a swim for recovering soldiers at the Sulphur Baths at Helouan and a trip to the Nile Barrage. On another occasion, a giant tea party was thrown for 2000 recovering soldiers. These photos tell the stories of the men who made it out alive, thanks to the work of the Red Cross and military medical services.

are all pictured. The images also show the preparations made at stations before the hospital trains arrived, the removal of casualties from the train and the carrying of the wounded on to ambulances. From the station the wounded were taken to hospital. The Queen’s Hospital for Sailors and Soldiers in Kent features prominently in this album. This was a place where men who had suffered facial or head injuries could be treated. From here, soldiers were moved to a clearing hospital in Eastleigh, Hampshire. The final stage of treatment was provided by convalescent homes, such as the Hotel Burdon at Weymouth. Convalescence might also mean a trip out. The Red Cross Outings Society of Cairo organised a swim for recovering soldiers at the Sulphur Baths at Helouan and a trip to the Nile Barrage. On another occasion, a giant tea party was thrown for 2000 recovering soldiers. These photos tell the stories of the men who made it out alive, thanks to the work of the Red Cross and military medical services.

Module IV: A Global Conflict

The Diary of Thomas Tweed

Callum McKelvie

By its conclusion, the First World War had been responsible for a horrific number of fatalities and casualties, lodging itself in popular consciousness as ‘the war to end all wars’. Within this collection, there are many letters, diaries and ephemera from a variety of individuals, many of whom tragically lost their lives in the conflict. These items allow the reader to build a picture of the individual up to the moment of their passing and serve to remind us of the horrendous human cost of the war. None are more effective at this than the small collection of items relating to Thomas Tweed, in particular, the unique piece featured here.

By its conclusion, the First World War had been responsible for a horrific number of fatalities and casualties, lodging itself in popular consciousness as ‘the war to end all wars’. Within this collection, there are many letters, diaries and ephemera from a variety of individuals, many of whom tragically lost their lives in the conflict. These items allow the reader to build a picture of the individual up to the moment of their passing and serve to remind us of the horrendous human cost of the war. None are more effective at this than the small collection of items relating to Thomas Tweed, in particular, the unique piece featured here.Socialism on the Steppe: The Russian Revolution Outside of Russia

Ben Jeffery

![[The memoirs of a Russian engineer serving in Tashkent, entitled 'Through War and Revolution' Part 1 Chapters I-VI]](/ContributeData/FirstWorldWar/Views/Introduction/Tashkent.jpg) The Russian Revolution, despite its name, was not solely a ‘Russian’ affair. The unrest and change of regime would have severe ramifications for other countries that, at the time, were part of Russia’s larger Empire. One such example is the geographical region of Turkestan, an area covering a vast swathe of Central Asia, home to a myriad of languages, ethnicities and religions. Since the 18th century Turkestan had been controlled by the Russian Empire, containing strategic battlegrounds in ‘The Great Game’. The memoirs of Russian Engineer V.F. Gniessen (Part 1 Chapters I-VI), based in Turkestan, offer an insight into why this region was so important during both the First World War and the Russian Revolution.

The Russian Revolution, despite its name, was not solely a ‘Russian’ affair. The unrest and change of regime would have severe ramifications for other countries that, at the time, were part of Russia’s larger Empire. One such example is the geographical region of Turkestan, an area covering a vast swathe of Central Asia, home to a myriad of languages, ethnicities and religions. Since the 18th century Turkestan had been controlled by the Russian Empire, containing strategic battlegrounds in ‘The Great Game’. The memoirs of Russian Engineer V.F. Gniessen (Part 1 Chapters I-VI), based in Turkestan, offer an insight into why this region was so important during both the First World War and the Russian Revolution.

The memoirs, encompassing six documents in total, describe the early years of the First World War, the actions of Russian soldiers in the region and engagements with German troops. Throughout the memoir, Gniessen details the deteriorating domestic situation in European Russia, but also the consequences this had in Turkestan. The memoirs reveal the Revolution as witnessed through the lens of events occurring in Turkestan; a viewpoint of this period very rarely heard.

Gniessen bears witness to the impact the fall of the Romanov dynasty had on Turkestan. He provides detailed commentary on the establishment of the Tashkent Soviet and the spread of Bolshevism in the region. While he recollects on the events of the Revolution as a whole, some of the most interesting passages are his in-depth and personal conversations with important individuals.

The later parts of the memoir (Part 2 Chapters VI-XI) describe the complex nature of the Russian Civil War. He notes the actions of anti-Bolsheviks in Turkestan and how they fought with a British Intervention force, comprising of both British and Indian troops, who had moved into Turkestan from Persia. Here, he highlights the struggles of these Russian and British soldiers in the wake of spreading socialism in the region.

Gniessen provides not only a commentary on the geopolitical situation in the region, but also places a very humanistic element to his recounting of events. In these glimpses into the personal, he describes his wife and family, his friends and his fears.

These documents provide an invaluable, and importantly, an English language source on a remarkable, yet tragic time that would set the course of history for Turkestan for future decades.